For sale, an Early Twentieth Century Snowdon Pattern copper rain gauge by Casella of London.

This simple yet effective instrument has been known as the standard for rainfall measurement since the 1860’s when the British Rainfall Organisation led by GJ Symons trialled a number of available instruments. According to Negretti & Zambra’s catalogues of the 1870’s this instrument was considered an improvement to the Howard’s rain gauge which consisted of a glass bottle with a funnel placed in the top. This earlier example was proven to be hugely vulnerable to failure in cold weather due to the exposed nature of the glass and the effects of freezing temperatures upon it.

To counteract this issue, Symons suggested that the glass bottle should be contained within a copper can which was to be partially buried in the earth to avoid surface temperatures on the glass, to maintain a level position and also to collect any spillage during extreme rain events. The cylindrical copper lid contains a funnel at the base with a tube that protrudes down into the glass measuring cylinder and the high surrounding sides were intended to reduce the amount of in-splash or out-splash associated with the landing of the raindrops and equally to allow for the collection of snowfall. Furthermore, the rim was surrounded by a piece of brass with a sharp knife edge lip to ensure that the catchment area remained as defined as possible.

Slightly later than Negretti, Casella’s catalogue of the 1880’s (although both organisations’ catalogues are surprisingly similar throughout) began to market this design where it was named, The Meteorological Office Rain Gauge” in reference to their use by this point as a standard for rainfall measurement.

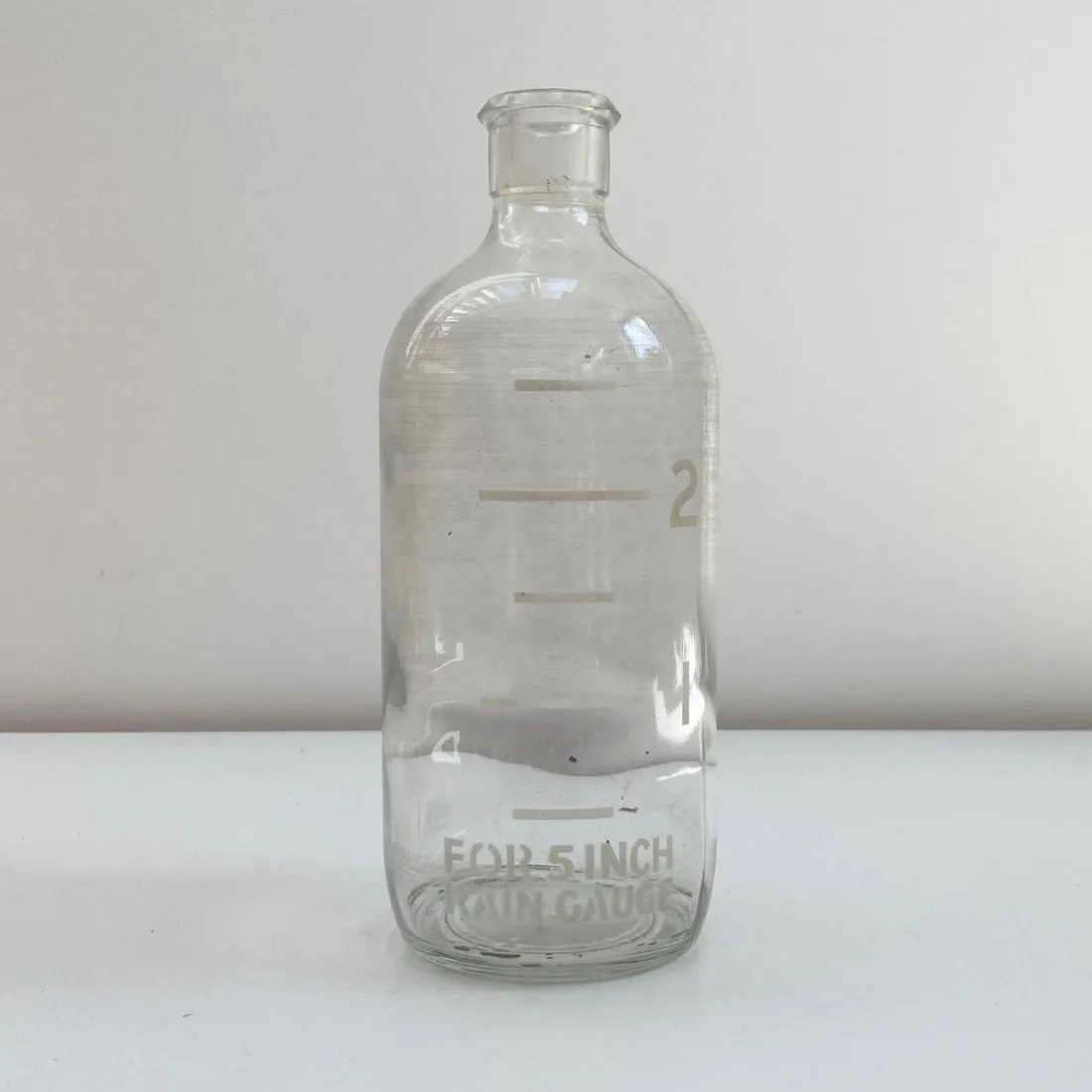

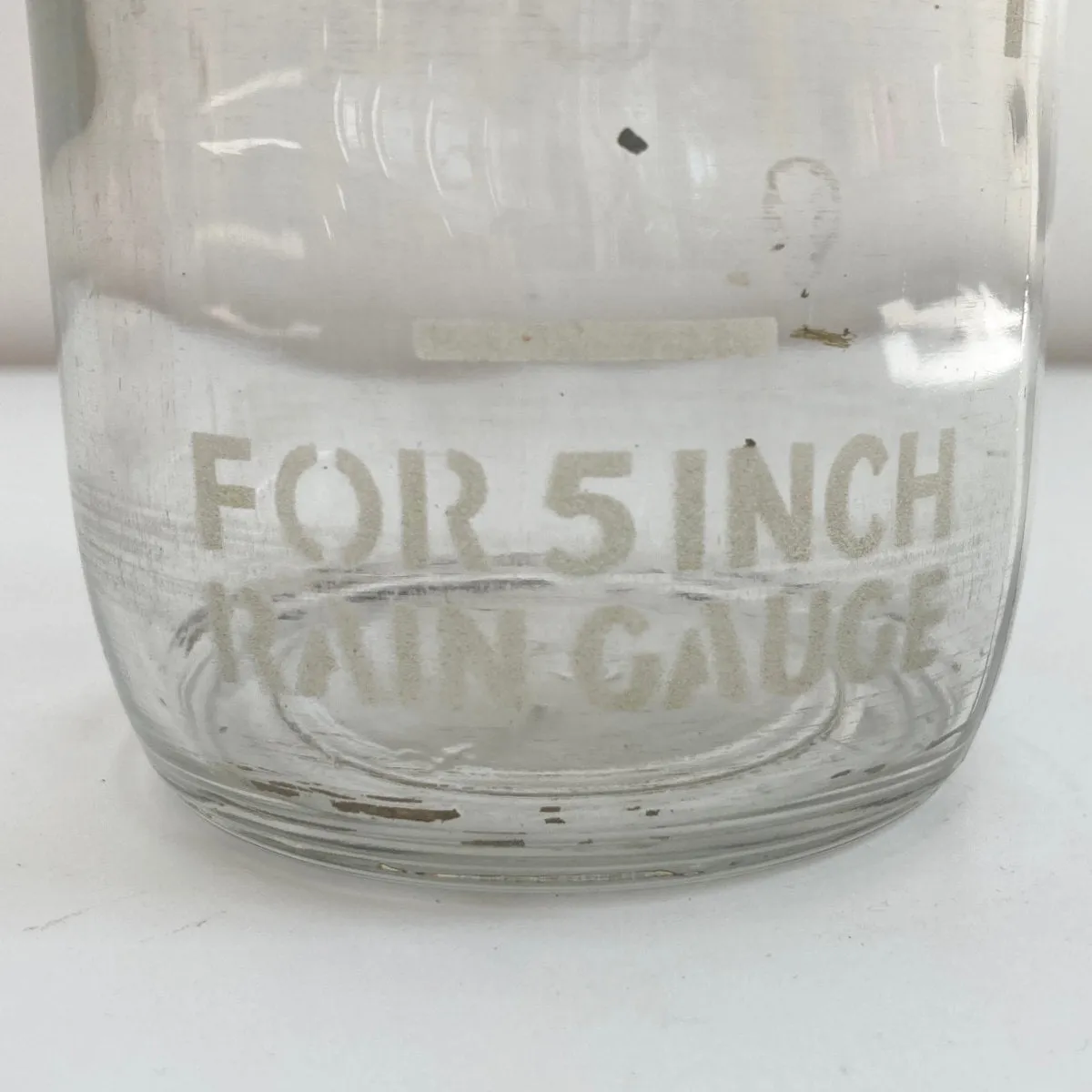

This example comes unusually complete with its original glass bottle etched with scale and the words “for five inch rain gauge” and internal copper bucket for lifting the cylinder out of the can for measurement. A fine example with Casella London brass plaque to the front.

Alongside Negretti & Zambra, Louis Casella’s company was at the zenith of meteorological instrument making during the Victorian period. Given their Italian origins, it is perhaps not surprising that like Negretti & Zambra, Casella also hailed from the Como region of Italy and he was very well acquainted with his competition.

Luigi Pasquale Casella was the son of a musician who came to The British Isles in the Early Nineteenth Century and the anglicised “Louis” was born in Edinburgh in 1812. His Father eventually rose to be a music tutor to George III’s daughters but by the 1830’s, his son had apprenticed to Cesar Tagliabue, a noted Italian instrument maker who had been in London since the turn of the century.

Casella eventually married Tagliabue’s daughter in 1837 and shortly after formed the partnership of Tagliabue and Casella with his new father in law in 1838. Tagliabue was already known to have been exporting his products to South America and Europe and must have provided Casella with a perfect grounding in both instrument making and more importantly in the business of selling them.

It is somewhat strange that this partnership should ever had existed given that Cesar is known to have had three sons, John, Anthony & Angelo but presumably his focus was on providing his daughter and her husband an equally good opportunity in life. The numerous Tagliabue’s listed in trade directories of the period would suggest that the family remained close knit in any case and the son John also went on to form an early partnership with Joseph Zambra prior to the latter’s more famous partnership with Henry Negretti in 1850.

Cesar Tagliabue eventually died in 1844 leaving the business to be solely managed by his son in law Louis Casella and the under his long stewardship became one of the most renowned scientific instrument making firms of the nineteenth century, providing products to the likes of Darwin and Livingstone. Cordial relations were almost certainly maintained with Negretti & Zambra over the years as Casella’s catalogue of the 1860’s shares numerous similarities with his competitor. Both were equally capable makers so it suggests that the parties were probably sharing manufacturing practises to create greater industry and both exhibited with great success at The Great Exhibition and the following Exhibition of 1862 where Casella was awarded a prize for his meteorological instruments.

By this point, his catalogues state that he was employed as an instrument maker to The Admiralty, The Board of Trade, Board of Ordnance, The War Department, The Royal Observatories at Kew and The Cape of Good Hope and numerous Governments and Universities.

Casella’s sons, Louis Marino and Charles Frederick both trained under their Father alongside other members of the Tagliabue family and also the latterly famous JJ Hicks who was perhaps the most promising of all of those that emanated from his workshop. He eventually died in 1897 whereafter Charles took over the sole ownership of the company.

Sadly, the younger son did not possess the same level of business acumen and skill as his Father and the business had become rather run down by 1905 but it was incorporated in 1910 and with the assistance of more adept management from Rowland Miall and Robert Abraham, manged to regain its momentum. The First and Second World Wars saw it engaged in numerous Governmental contracts but also saw the deaths of both of Casella’s sons, finally severing the link with the original family.

Casella is one of the few companies of this period that still remains in existence today, it continued to provide meteorological instruments throughout much of the Twentieth Century but the focus of the business has since diversified into environmental sampling and monitoring products.

Circa 1910